Hiroshima mon amour, written by Marguerite Duras and directed by Alain Resnais, “was a cinematic shock whose repercussions continue to this day” 1 If it is possible to gauge the extent of this through the many texts by film critics that have paid tribute to him, the publication of the screenplay in Gallimard’s famous “Blanche” is a remarkable manifestation of this, illustrating the scope of the transgression that this aesthetic event represented.

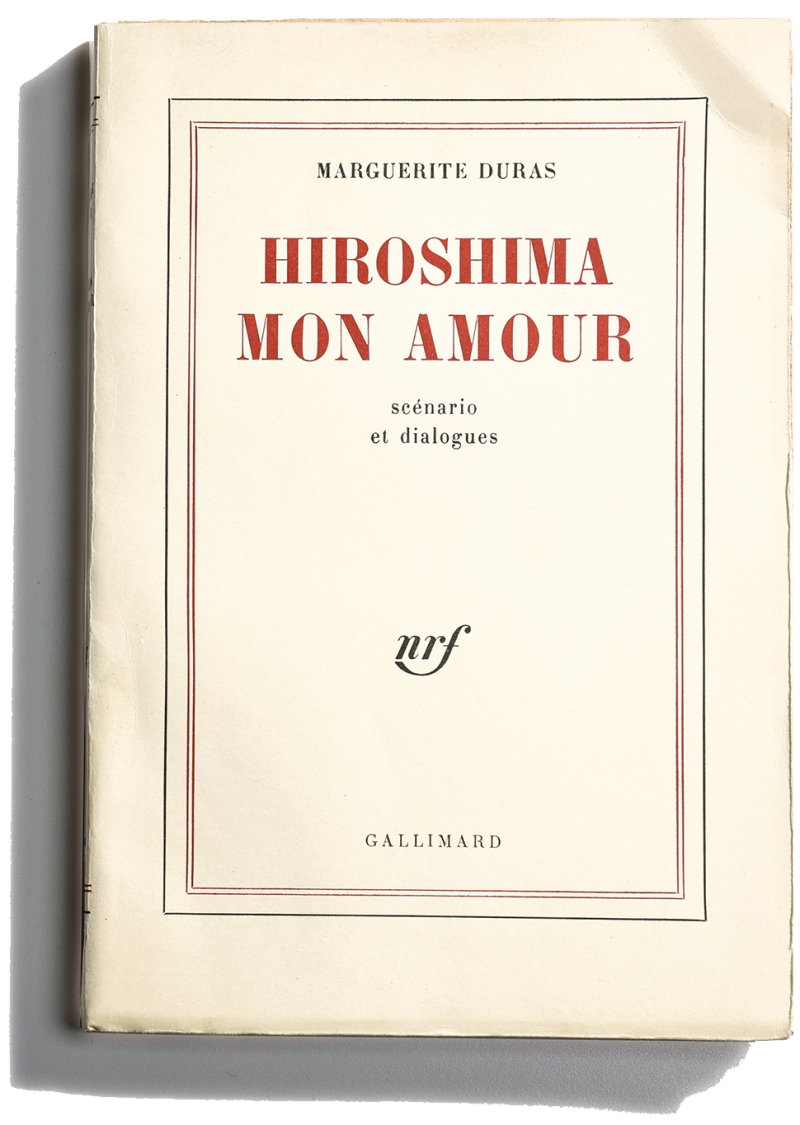

Written in 1958, the screenplay Hiroshima mon amour marked Marguerite Duras’s entry into the world of cinema. Twenty months later, when it was published by Gallimard, the screenplay became a new literary genre. The layout of the book, which is classic and unobtrusive and in keeping with the visual principles of the collection, is exceptional in that it contains photographs alongside the text. Like the appendices recounting the genesis of the film, the relationship between the text and the image reveals, like a sensitive surface, the foundations of his cinema in the making. In many ways, this book of origins is a graphic beacon for Histoire(s) du cinéma by Jean-Luc Godard, a major publishing venture published forty years later in the same collection.

The power of books

“They were alive, they spoke to me (...) Isn’t that a strange thing to say, when you think that books are made of signs and symbols” It was in these powerful terms that Henry Miller evoked the books of his life 2 The book Hiroshima mon amour, in its first edition published in Gallimard’s ‘Blanche’ series in December 1960, is just as compelling a summons. “How could I have suspected that you were the size of my own body? I like you. What an event. I like you” says the woman from Nevers. And what better way to get away from both the text and the film – “which has become a double classic in the history of cinema and the history of literature” 3 than to approach it from its physical side, with its weight and matter, inscribed in the thickness of time, to grasp what is still pulsating, so intensely, in these printed pages?

“Something has taken place that has inscribed itself, with all the force of its presence, in the order of thought” 4 says Nathalie Léger, to define the place of the archive. “It is what remains (...) but it is also, as the etymology says, what begins.” And this book, in particular, calls for such an unfolding. The supplements to the dialogue that are the appendices 5 form an indissociable whole that reveals “the literary part of the artistic process that led to the cinematographic work” 6 says Robert Harvey. The modus operandi adopted in unison by Resnais and Duras in developing the film and writing the screenplay is formulated in these terms by its author: ‘the work I did on this subterranean continuity of the film is at least as important as the work I did on the continuity itself. What is shown is doubled by what is not shown. 7 How do these different continuities coexist on the page? What graphic layout has been adopted to make them present? How do the text and photography respond to each other? Following Duras’ trail, but a trail that is “still fresh, barely made, when the work vibrates with this beautiful uncertainty” 8 In the words of Alain Bergala, referring to the work of one of his contemporaries - Jean-Luc Godard - this is the path that will be explored to make explicit in the graphic form of Hiroshima the features that will characterise the cinema of Marguerite Duras. Taking this diversions via Godard, given the singular and sometimes shared paths that lead these two authors from print to cinematic expression, seems particularly fruitful. From film to book and from book to film, Duras and Godard take paths that are sometimes parallel and sometimes reversed. When confronted, they provide keys to deciphering what lies beneath the surface of apparent meaning.

Writing for the cinema

On this question of imprint and inscription, Marguerite Duras used these words to comment on her own text: “For me”, she said, “Hiroshima is a novel written on film” 9 In 1987, in a dialogue between the director and the writer that was to become a television landmark 10 — the meeting, according to Godard, of ‘two rocks’, one from literature, the other from cinema — the filmmaker agreed with her, recognising her rare status as writer-filmmaker: a small circle he called “the gang of four”, in which Duras – the only woman – figures alongside veterans Jean Cocteau, Sacha Guitry and Marcel Pagnol, all three from a generation before Godard’s and already buried at the time of the interview. Was this a provocation on the part of the filmmaker to contradict his peers? Nevertheless, the recognition of her cinematographic work and the authority he confers on Duras – writer and woman – deserve to be underlined.

Taking as its starting point Hiroshima mon amour, a source book in more ways than one, which reveals in its pages the beginnings of its author’s cinema in the making, takes on its full meaning in the light of that essential horizon line that is Histoire(s) du cinéma, which was also published in four volumes in the ‘Blanche’ series in 1998, almost forty years apart.

In addition to their common membership of the Gallimard collection, the two works have as points of convergence cinema and history, war and love, and through their poetic narrative form and their text/image relationship maintain a singularly attuned alliance between memory and oblivion, erasure and presence.

When the seventh art is being read

Although screenplays were published in the specialist press in the 1950s, the publication of Hiroshima, accompanied by appendices, was in 1960 “a sign of the growing prestige conferred on the work of writers for the cinema”, 11 marking a new position in publishing with regard to the seventh art. In the “Blanche” collection, Marguerite Duras published two other screenplays: Une aussi longue absence (1961), co-written with Gérard Jarlot, and Nathalie Granger followed by La Femme du Gange (1973).

The transition from film to book for Hiroshima mon amour took twenty months, as indicated by the print proof dated 6 December 1960, the film having been presented at Cannes in the spring of 1959. The gestation period was long enough for the publishing house, through its brand new artistic director, Robert Massin, to carry out “a sovereign and quiet revolution”. 12 In all its restraint, the upheaval in graphic form introduced by this Gallimard publication demonstrates the publishing house’s ability to embrace the zeitgeist by incorporating the momentum of the New Wave, which François Truffaut claimed at the Festival had begun with Hiroshima, and other films such as Jean-Luc Godard's À bout de souffle (Breathless).

The graphic envelope: sober and enchanting

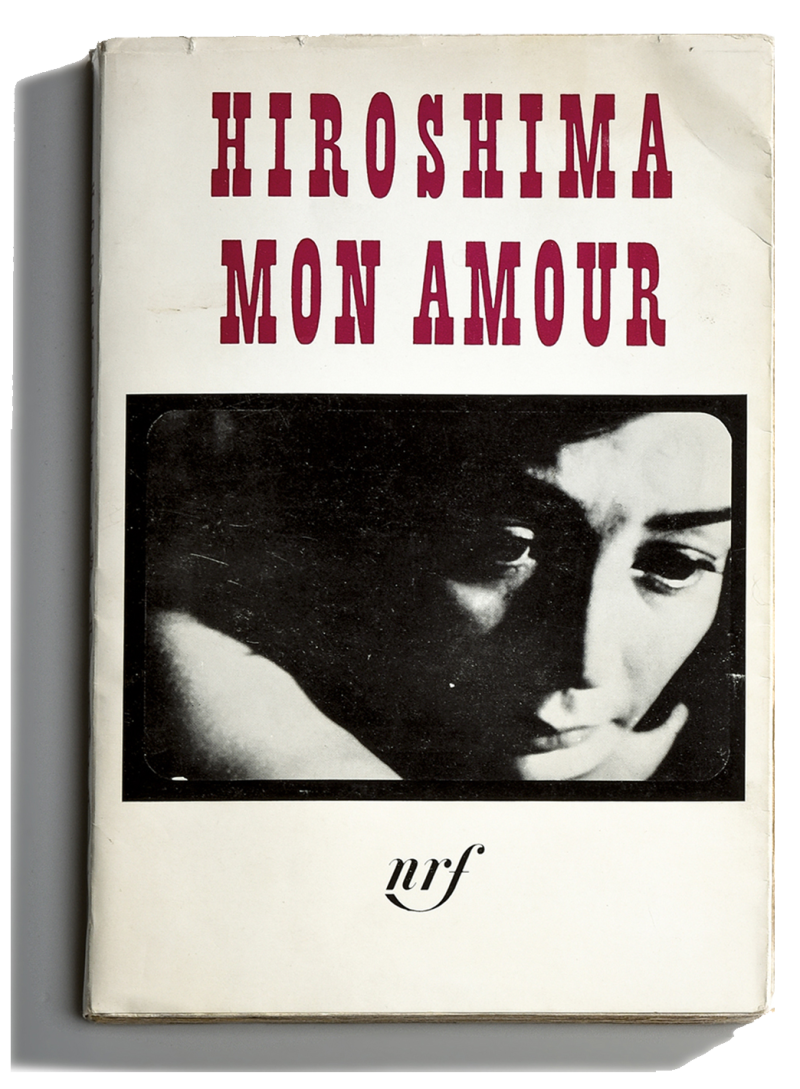

Even before entering the book and tackling its layout, its cover is a must. Sober and bewitching, the original dust jacket of the 1960 edition makes a strong impression. Served by a limpid composition, it frankly appeals and seduces the eye. The notoriety of the film, surrounded by “scandalous success” 13 even before its release in 1959, contributed to the success of this minimal, incisive effect.

The title, all capitals, red tinged with fuchsia, in a slightly incongruous Western like font printed on glossy paper of an almost bluish whiteness, stands out as it should with just the right amount of strangeness. The close-up of actress Emmanuelle Riva’s face, in a very dense black and white, reinforces this feeling. “Everything about her, from words to movement, passes through the gaze”, Marguerite Duras once remarked. And that is precisely what this portrait captures, a gaze that is “oblivious of itself”. ‘This woman looks for herself. Her gaze does not consecrate her behaviour, it always overflows it 14 The same is true of the cover photograph, which seems to escape from its black frame, depicting the projection room. The elegant NRF (Nouvelle Revue Française) monogram (a redesigned italic Didot) is added to this still from the film, faithfully reproduced in its original framing, placed in a centered position, that of a large house representative of the French intelligentsia.

Like the film, this graphic envelope is part of a break with the past. In Gallimard’s “Blanche” collection, described by art historian Catherine de Smet ‘as the most characteristic example of mainstream French publishing, isolated (...) in an unchanging tradition directly inherited from the Age of Enlightenment, and impervious to any spirit of innovation 15 “Hiroshima paves the way for a series dedicated to the screenplay, which will include a dust jacket and the reproduction of a film image” 16 says Gallimard historian Alban Cerisier. In the immediate aftermath of this publication, in addition to Une aussi longue absence (Henri Colpi, 1961), the same graphic principle was used for René Clair’s Tout l’or du monde (1961); Jacques Audiberti’s La Poupée (Jacques Baratier, 1962); Truman Capote’s Petit déjeuner chez Tiffany (Blake Edwards, 1961), which was not published in French until 1962; and Jean Vauthier’s Les Abysses (Nikos Papatakis, 1963).

The author of the dust jacket is none other than the graphic designer Massin. Having joined Gallimard in 1958 as artistic director, Massin had already experimented extensively at the Club français du livre, where he had worked since 1948, and his so-called expressive typography layouts, including that of Eugène Ionesco’s La Cantatrice chauve (1964), which was a landmark in the history of books. As Laetitia Wolff put it: “If there is one constant in Massin’s work as an art director, and particularly in his work for Gallimard, it is the white background, an echo of ‘the famous, and still extant, “Blanche” collection, the most characteristic example of current French publishing.” 17

Born in 1911 with the first titles published by Éditions de la Nouvelle Revue française (NRF), this collection of French literature and criticism owes its name to the ivory tint of its cover, “in stark contrast to the vivid solid colours of the current production of publishers at the turn of the century”, according to the history provided by the publishing house. And Massin adds that it was white, “in the minds of its promoters, only by way of contrast, if not protest. (...)” The “Blanche”, he says, is a permanent illustration of the refusal to take the easy way out, inherited from publishers such as André Gide, Jean Schlumberger and Gaston Gallimard, and it is at the same time the height of elegance. 18

Another peculiarity of this inaugural packaging is that the cover bears no name. Neither Alain Resnais nor Marguerite Duras are mentioned, as if the authorship of the work were indistinguishable. “Rarely has there been a cinematographic work in which poetic dialogue has been so important, so much so that today Hiroshima mon amour is recognised as much for its literary value and associated as much with Marguerite Duras as with Alain Resnais, the director” 19 recalls Robert Harvey. And this anonymity, which can be ruled out a priori as the result of an omission, remains rather enigmatic. In the dust jackets that followed Hiroshima mon amour, this editorial oddity of not including an author’s name was only repeated once, and in the immediate aftermath of this publication, with Une aussi longue absence, which had at its heart the same ‘dialectic of memory and forgetting’. 20 The same year, 1961, Henri Colpi’s adaptation of this screenplay won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and the Prix Louis-Delluc. The similarity of the context, the two hands working together, the common theme and the contiguity of the texts seem to have favoured this graphic twinning.

For Hiroshima, we can assume that this editorial choice comes from the desire of the filmmaker and the screenwriter to highlight the common work, the collective work. This absence of names also perhaps marks the refusal of the authors to categorize their tasks and to prioritize them. Unless, more prosaically, the film released twenty months earlier was already strongly associated with the name of Resnais and to mention only the name of Marguerite Duras alongside this title would have risked sowing confusion. This blank finally, a posteriori, serves our purpose, materializing the indefiniteness of the role played by the writer who, from “filmmaker with a pen” 21 alongside Resnais, would move on in 1967 alongside Paul Seban to co-direct La Musica, based on a text of which she was also the author. Before that, she had participated in 1964 in the adaptation of the television film Sans Merveille by Michel Mitrani produced for ORTF. It was in 1969 that, text and direction, she signed her first cinematographic work as a director with Détruire dit-elle. We know how Marguerite Duras’ foray into cinema, although late, was assiduous, giving rise to a production of nineteen films 22 concentrated between 1969 and 1985.

The look of the book

Compared to this first edition of 1960, which plays on the quality of papers of different types — coated for the photographs, bulky for the text — the editions published later in the “Blanche” erase this contrast even if a slight distinction remains. Time, it is true, has accentuated the contrast between the two papers, in their color and in feel: white and glossy for the photographs, yellowed and almost damp for the text, close to a newspaper full of the relief of lead printing. The untrimmed pages (characteristic of the period) add to the texture of the book. Massin will recognize in this regard the noticeable change that trimming caused in the grip of the object: “I am responsible, for having generalized it at the same time for almost all of Gallimard’s production, for the trimming of the volumes. Have I been criticized enough for it! (…) it is true that an uncut book has a charm, an appeal, an “intimacy” (…) which a book trimmed to the quick on three sides lacks. (…)” 23 The polished appearance of the editions that followed would make the book lose that grip that particularly suited Hiroshima mon amour.

This first layout also left plenty of room for white, for areas of silence that were favorable to the circulation of the eye, easily navigating from text to images, like a distant echo of Paul Valéry’s text in the face of Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (A throw of the dice will never abolish chance): “Waiting, doubt, concentration were visible things. My sight was dealing with silences that had taken shape” 24

About this blank that represents silence, we can also transpose what Marguerite Duras said during an interview on Détruire dit-elle: “The music [The Art of Fugue by Jean Sébastien Bach] in fact ends the book — like the film — and what is said at that moment relates to it alone. It is it that decided the metrics of the film (…). Thus the silences correspond either to the duration of the sentence, or to multiples of it. (…) I never stopped “hearing” this music throughout the film and for the entire team it was a conditioning.” 25

By contrast, we discover in the Pléiade edition, published in 2011, presenting the complete works of Marguerite Duras (from 1943 to 1973), that this dimension is totally ignored. The images have clearly been placed where they could be, following the text and in the most exact vicinity of the initial edition. Conformity to the original textual and visual elements seems to have been the only criterion that prevailed, stemming from a concern for documentary exhaustiveness, which is open to question. While it is essential in the tension and rhythm that are created with the text, the white space is in fact judged to have no informative value, and disappears in favor of maximum filling and without breathing. By thus distorting the layout and the text/image relationship present in the original edition, the publisher indirectly allows the reader to measure the precision of the intentions of the initial composition.

Layouts, in the original edition of the *Hiroshima mon amour* screenplay (left side, bigger format), and in its reproduction in the Pléiade (right side, smaller). Photos: Nathalie Guyon.

While acknowledging the merits of the Pléiade, Massin thus points out its “small volume, sale price generally lower than the sum of the price of texts in current edition” but regrets the leveling imposed by the principle of collection: “For my part, it is difficult for me, even unpleasant, to read Rabelais composed in Didot and, conversely, Victor Hugo in Garamond, in the same way that I would not use the same character depending on whether it is Proust or Céline, Claudel or Prévert, Balzac or Rimbaud, etc.” 23

Not a graphic designer’s book, a printer’s book

While Hiroshima mon amour imposes itself as a graphic object, a tangible material on which to lean, the book allows its layout to emerge without ostentatious insistence.

As we’ve seen, the main characteristic of this book is its place in the “Blanche”. It is not a book by a graphic designer, nor is it the singular production of a writer taking on the role of graphic designer. Its meticulous layout offers no salient features to tie in with. As for the photographs, apart from their infrequent presence in the collection, Marguerite Duras is not the author either.

On the other hand, the writer does allude, significantly if evasively, to typography, in an interview with Xavière Gauthier in Les Parleuses, where she evokes a wish she leaves unfulfilled: “If we could keep silence in typography...26 A concise wish that seems to find its most appropriate form in the “Blanche”, a collection that, from the outset, was “based on a categorical refusal of decorative treatment in favor of intact legibility, favoring typographic unity and sobriety of composition”. 27

What role did Duras play in the graphic design? If we confine ourselves to the typographic composition - we’ll come back to the text/image relationship she establishes with the addition of photographs – we can assume that it was minimal, the typeface being invariable and the layout modeled according to a more or less standardized template. “(...) At Gallimard, everything was still done at the printer’s. 28 In all likelihood, this is what happened, with the approval of Massin, who had been in office since 1958.

Regarding the Garamond used in several Gallimard collections, Massin acknowledges the validity of such use: "I am also willing to admit that characters such as elzevirs have a timeless vocation insofar as they were the first to be designed (if we leave aside the Germanic countries) for typography, and that they did nothing more than reproduce the writing of scribes at the time of the invention of printing; and that even today, America, the country (...) of all graphic audacities, continues to use Garamond (or the fifty or so variants offered by type manufacturers) for most printed matter, current books, news, newspapers or advertising texts. 29 At the letter of the collection, Marguerite Duras adopts its whiteness, occupies this sobriety and makes this “categorical refusal” her own by displacing it. Which, as Massin points out, regarding so-called neutral typography, could explain the shift that occurs in the composition in resonance with her text: “It seems to me, however, that characters that seem neutral, by a design that does not draw attention, or by the gray or discreet color of their fat, are not always innocent. (As we see, everything is political.)” [ ^ Ibid.]

Photographs and mental images on the page

The presence of photographs—thirty-three in number—in a collection and a category (the film script) that only included them on very rare occasions also characterizes the book Hiroshima mon amour. It was preceded by a single work, Le Film de Béthanie (1944), by Jean Giraudoux, which includes six images, and which would inspire Les Anges du Péché by Robert Bresson. In addition to situating Hiroshima and emphasizing its novelty, this chronology of publications allows us to measure the importance that such a proximity could have had in the writer's first cinematic steps. Especially since for Duras, Bresson was “one of the greatest who ever existed.” Pickpocket, Au hasard Balthazar, she would affirm, could alone be the entire cinema30 In 1961, in the wake of Hiroshima, Une aussi longue absence also included photographs, thirty-two in number, from the film shot by Henri Colpi. However, there was a major difference between them in terms of relationship between text and image: unlike Hiroshima, the photographs in the second book were all brought together in a single notebook, at the beginning of the book after the titles and the foreword, a principle that would also be adopted for René Clair’s next screenplay, Tout l’or du monde. The simplification of the layout and the cost must have presided over this choice of production. However, this rationalization did not open up a systematic path to photography in the “Blanche” collection. In Hiroshima, two types of photographs coexist, which are mainly photograms taken from the film. Alain Resnais, Robert Harvey recalls, had “his two directors of photography, Japanese and French, work in a watertight manner. Michio Takahashi filmed in Tokyo and Hiroshima and Sacha Vierny in Nevers and Autun. The two photographers used different brands and qualities of film and, above all, Resnais refused to let Vierny see what had been filmed in Japan, for fear that he would be influenced by it. 31 Similarly, just as he did with his two directors of photography, “Resnais wanted Duras to imagine these scenes of provincial life under the Occupation without participating in their visualization.” 32 In fact, she would only see the film once it had been edited. Which would make Duras say: "What I have learned quite simply is that cinema is no different from the other arts and I am happy about it…” 33 For two thirds of them, the photographs are distributed among the five parts that make up the entire screenplay. As for the ten or so remaining images, they are concentrated in one of the sections of the appendices entitled “Les Évidences nocturnes (Notes sur Nevers)”. A part where Duras, following Resnais’s instructions - “Act as if you had already seen the film and tell what you see” [^ Ibid.] – takes charge of the literary part and confronts, a posteriori, in this form of editing that is the layout, the photographs of the film with the “subterranean continuity” 33 that she had established to give birth to them.

For example, the following two double pages, whose photographs are arranged on the front and back of each other, show this continuity at work in the layout (see below).

The first image shows a square in Nevers with severely trimmed trees. On p. 110, the text says: “Nevers, where I was born, is indistinct from myself in my memory.” The second photograph on the back is of Emmanuelle Riva, embodying a woman who had her head shaved at the Liberation. On p. 111, Marguerite Duras describes the young woman in these terms: “She has the pose of a woman in desire, shameless to the point of vulgarity. (…) Disgusting. She desires a dead person.” And her outfit will be described as follows: “Lace nightgown, for a very young girl, made by the mother, by a mother who always forgets that her child is growing up.” The succession of the two images invites an analogy between the two cuts made, one on the trees whose branches stand like stumps, the other on the skull of this 18-year-old woman, savagely punished for having loved a German soldier.

In this other example below, the bringing together of the images and their relationship to the text form a visual composition that is all the stronger because it is refined.

The first image leaves a hole in the page, filled on the next page by the woman from Nevers, shaved, destroyed, in her turn in ruins after the death of her lover. The abysmal white mass of the sky is matched by the paleness of a face, a well of light emerging from the cellar. What the text says: “We first met in barns. Then in ruins. And then in rooms. Like everywhere.” The couple of clandestine lovers can barely be distinguished at the edge of this gap that represents the abyss into which they will sink.

The decision to adopt a very dense black and white for the image on the jacket is not repeated on the inside pages, where the typographic gray matches the photographs printed in more subtle shades of gray. In this range of colors, neither of the two modes of discourse—text and image—predominates visually over the other. A relationship of equality between the two constituents is as if instituted by this graphic treatment.

Even if nothing allows us to attest to it, we can imagine that Marguerite Duras was at the initiative of this marked editorial choice, because exceptional, of adding photographs to the different types of stories, and of their placement in the book, opposite the text. Three types of framing are adopted, including two main ones: the original one, in the majority of cases, faithful to the photograms from the film. The second corresponds to the enlargement of a detail which then occupies a full page in the book. And finally the third, a unique occurrence, of a square format, is, in all likelihood, a photograph of a scene from the filming (see below).

From word to image: cinema at work

From this first scenario, Duras will maintain a renewed relationship with photography in relation to writing and will conduct experiments similar to that of Hiroshima, but this time on one of her own novels — The Ravishing of Lol. V. Stein —, and as the sole master on board. She reports on it in 1968 with acute precision, images in support, in the program entitled “Chambre noire”, 34 produced by Michel Tournier and Albert Plécy. Usually oriented almost exclusively on the work of a photographer, the program is this time devoted to a “writer’s experience”. With the collaboration of photographers Jeanik Ducot and Jean Mascolo, and actress Loleh Bellon, Marguerite Duras undertook the production of a series of photographs based on her novel: “(…) I wanted to see if I could get closer to my inner vision, to the vision of places, things and people that I had when writing the novel. Obviously this mental vision, this mental image, which is parallel to writing, you can never completely find it again. What you can find are parallel places, parallel images, parallel characters, things that could have been imagined by you, of the same nature”. Marguerite Duras nevertheless remained on the threshold of cinema: this “very close approximation” achieved with photography and its almost perfect adequacy with the text would not give rise to a film adaptation. No one would propose a film adaptation, neither Duras, nor other directors (Joseph Losey was potentially in the running). During the same year, 1968, Duras would however take the plunge with another of her texts, Détruire dit-elle.

As a book-object intimately linked to the preceding film, to the musicality of its dialogues as much as to its images, does Hiroshima not lend itself even more than the film to materializing these parallel places of which the author speaks, and to bringing out the subterranean part of the text and images? Far from being a fixation, its “book-making” brings forth this mental vision and acts as a springboard to open the imagination.

In this neighboring operation that is the layout, Marguerite Duras identifies what the editing engenders, and what its physical imprint and its inscription on the film reveal:

“La Femme du Gange is two films: the film of the image and the film of the Voices. The film of the image was planned. It comes out of a project, its structure was recorded in a script. (…). The film says: the film of the Voices was not planned. He arrived once the film of the image was edited, finished. He came from far away, from where? He threw himself on the image, entered its place, remained. Now the two films are there, with total autonomy, linked only, but inexorably, by a material concomitance: they are both written on the same film and see at the same time”. 35

Like the film, the page also becomes the place of this “material concomitance.” The specific brilliance of this first edition of Hiroshima lies in the memory of the film mixed with the evocative power of its text, both of a rare intensity, whose layout, without heavy relief, is conducive to bringing out what is underlying in a process analogous to cinematographic editing, as described by Duras. Here, what Godard also designates as the emergence of the third image generated by this editing operation could be applied particularly to this layout of Hiroshima, in its resonance with the film: “(…) it is not one image after another, it is one image plus another which forms a third, the third being formed by the spectator.” 36

In this, more than a screenplay and its dialogues, this publication marks a decisive step in Marguerite Duras’ formal journey towards cinema — a field of experimentation just as fertile as literature — whose contours and limits she would never cease to question, notably in this accompanying text to the film Le Camion, in 1977: “Cinema knows it: it has never been able to replace the text. It nevertheless seeks to replace it. That the text alone is an indefinite bearer of images, it knows it. But it can no longer return to the text. It no longer knows how to return. It no longer knows the path to the forest, it no longer knows how to return to the unlimited potential of the text, to its unlimited proliferation of images (…)” 37

However, in this form of disavowal, as Jean Cléder points out, “[the] negation of the powers of the seventh art is very ambiguous, since it takes place in a cinematographic or peri-cinematographic framework”. 38

From ‘Hiroshima’ to ‘Histoire[s]’: what the layout reveals about cinema

Who better than Godard could understand this ambivalent relationship between Duras and the moving image? As a regular spectator of the printed word, Gérard Blanchard—a graphic designer, essayist, and teacher, among other multiple roles—had established this connection between the filmmaker and Duras, due to his interest in Godard’s graphic cinema, on which he produced a certain number of writings, in the form of notes, which can be consulted in the collection in his name at the Imec (Institut Mémoires de l’édition contemporaine). For example, two reviews of Cahiers du cinéma are preserved there: issue 300 (from May 1979), designed and edited by Godard and annotated by Blanchard, and Les Yeux verts, double issue 312/313 (from June 1980), arranged by Duras. The two publications share a common way of assembling text and images, posed rather than frozen, provisional and almost casual, as if thought remained in motion, and a visually striking choice of photographs. “It started with a series of interviews that they [Les Cahiers du cinéma] did with me, then they wanted direct interventions, finally we decided that I would coordinate the entire issue that was entirely devoted to me. (…) It was Godard who gave me the idea”, 39 Duras confided. Unlike Hiroshima and Histoire(s), Duras places herself with this magazine in the graphic wake of Godard, who preceded her by a year with the publication of issue 300.

In “La Blanche”, on the other hand, the contrast in the layout is particularly striking. Where Duras is part of the visual principles of a collection, Godard, with Histoire(s) du cinéma, imposes a radical break with the established layout. Regarding this work in particular, and the first layouts presented by Jean-Luc Godard in 1995, the testimony of Jacques Maillot, then artistic director of Gallimard, is eloquent. It was “neither an illustrated book nor a film book in the classical sense,” he would say, “but a work ‘written’ with words, images, blank spaces, typographical spaces.” In Histoire(s) du cinéma, no rule of template is respected: “The layout corresponds to the phonetic unfolding of words in films. (…) Sometimes the images are closer to the text so that we associate them better mentally, in other places he moves them away to build another relationship between them, and with the reader. I don’t know of any comparable work on a book”, 40 he concludes. The filmmaker also chooses Bookman as a font (drawn by the American, Ed Benguiat), because of his name — “There you have it, ‘the book man’, that’s what’s needed” 33 Finally, the last major departure from the immutable “Blanche”, that of imposing an image on the cover of each of the four volumes. Let us cite two precedents in the collection: 41 Paris by Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz (1939) and L’Œil écoute (The Eye listens) by Paul Claudel (1946).

Regarding L’Œil écoute, Godard, despite everything being part of a historical continuity of “La Blanche”, will underline how much the existence of this precedent will have served his argument to persuade the publisher to accept an image on the cover: “I showed Antoine Gallimard an old edition of L’Œil écoute by Claudel where on the cover there was a very small image. And that won the decision. Thanks to Claudel!” 42

But if, as we have seen in Hiroshima, unlike Histoire(s), there is no graphic brilliance, it is because the need for rupture does not obey the same springs. The question of authority arises distinctly for Duras and Godard as authors in the “Blanche”. Duras has this dual status of writer and filmmaker while Godard establishes himself as a monument of the seventh art. This coup de force of bringing cinema into the “Blanche” in this graphic form, Godard would proclaim with satisfaction again very recently, in 2013: “Yes, I am a Gallimard author”. 33

One of the major formal differences that distinguishes Duras from Jean-Luc Godard is her lack of recourse to quotation or collage. In the television interview cited above, Duras tells him: “There is something in the principle of writing that attracts you on the one hand and, on the other, annoys you and makes you flee. You can’t stand up to writing. (…) You make a film first, then you try to solicit speech” 43 Why does Marguerite Duras use this word, “racoler” (to solicit)? Is she pointing out his charlatan side? Does he cite texts to impose themselves, as this verb seems to suggest? These are the questions that Georges Didi-Huberman will formulate in a seminar that he will call “Passés cités/pas cécité (French word game, “Past quotes / not blindness”) by Jean-Luc Godard 44 where, he recalls, the filmmaker’s work is an immense constellation of pasts cited to open eyes, to resist blindness. Would Godard be showing off by citing? “I recognize this side of pandering, but not anymore,” he will say as a response to Marguerite Duras. He would also cite the latter’s cinematographic work on numerous occasions in his films 45 notably in Histoire(s) du cinéma, where a cropped frame of Hiroshima appears in volume IV. Did Godard choose it from the film or was it the still image in the script that caught his attention? The question arises even if in Histoire(s) the treatment of the image differs and the framing is clearly tighter on the face, as if in ecstasy, of Emmanuelle Riva.

By not citing, Duras is neither in competition nor in irreverence. By her refusal to place herself in a wake, to swear allegiance, to give way to recognition, she thus neutralizes any inscription, even if her films contain numerous and emphatic allusions to certain filmmakers (Ingmar Bergman, Robert Bresson, Jean-Luc Godard, Straub and Huillet, for example).

With these words, Hélène Cixous, in an interview with Michel Foucault, 46 allows us to explain the meanings and contents detected in the formatting of Hiroshima, which will irrigate her future cinema.

You haven’t seen anything

Among the many avatars that the text underwent, Hiroshima mon amour took place in a radio program entitled “Histoire sans images” 47 whose title did not fail to appeal so much in the “Blanche,” Hiroshima mon amour is seen as a workroom for images.

Tu n’as rien vu (“You haven’t seen anything”) or what five words can do for memory. “You haven’t seen anything” was one of the titles considered for the film Hiroshima, whose elliptical introduction, reactive for those who, only once, have heard, read or seen it, a refrain cut to be engraved in the memory. More than fifty years later, Vous n’avez encore rien vu (You Haven’t Seen Anything Yet) will become the title of one of Resnais’s very last films, released in 2012. The incantation is repeated, but in the meantime, the address has changed, the promise of enchantment still burns, even if the erotic intensity has been lost. And no, we haven’t seen anything. And it is to this suspension, infinite and haunting, that this book and its subterranean images refer again and again.

Paule Palacios-Dalens has a doctorate in aesthetics and history of the visual arts. Her research focuses on the relationship between cinema, books and typography. Since 2014, she has collaborated as author and graphic designer with 202 éditions, which publishes essays on cinema. In 2003, she was awarded the “Bourse Agora” design prize for a project at the ANRT, Atelier national de recherche typographique, involving the design of television subtitles for the deaf and hard-of-hearing.

- Matthieu Rémy, “Le choc Hiroshima mon amour: Guy Debord, Georges Perec, Serge Daney” in Marguerite Duras, Marges et transgressions, Actes du colloque des 31 mars, 1er et 2 avril 2005, Université Nancy 2 - UFR de Lettres (texts collected and presented by Anne Cousseau and Dominique Roussel-Denès), Presses universitaires de Nancy, 2006, p. 195-204. ↩

- Henry Miller, Les Livres de ma vie (The Books of my Life), ‘L'Imaginaire’, Gallimard, 1957, p. 47 ↩

- Robert Harvey, notice de Hiroshima mon amour in Marguerite Duras, Œuvres complètes, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, Gallimard, 2011-2014, II, p. 1650. ↩

- Nathalie Léger, “Le lieu de l’archive” (preface), Supplément à la Lettre de l'Imec, 2012. ↩

- The appendices are divided into four sections: “Evidences nocturnes (Notes on Nevers)”, “Nevers (Pour mémoire)”, “Portrait du Japonais” and “Portrait de la Française”. ↩

- Marguerite Duras, Œuvres complètes, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, Gallimard, 2011-2014, II, p. 1650. ↩

- Ibid. p. 117. ↩

- Alain Bergala, Nul mieux que Godard, Essais series, Cahiers du cinéma, 1999. ↩

- Marguerite Duras, “Les hommes de 1963 ne sont pas assez féminins”, Paris-Théâtre, no. 198, 1963, p. 37, reference given in Œuvres complètes, 2011-2014, II, p. 1639. ↩

- Duras-Godard, «Océaniques», 28 December 1987. ↩

- Marguerite Duras, Œuvres complètes, 2011-2014, II, p. 1649. ↩

- Philippe Schuwer, “Les avatars du livre”, Massin, textes et témoignages de Bernard Anthonioz, Roland Barthes, François Billetdoux... (et al.) réunis par André Derval, Imec Éditions, 1990, p. 94. ↩

- Marguerite Duras, Œuvres complètes, 2011-2014, II, p. 1631. ↩

- Marguerite Duras, “Travailler pour le cinéma”, France-Observateur, 31 July 1958, quoted in Marguerite Duras, Œuvres complètes, II, p. 113. ↩

- Catherine de Smet, on Robin Kinross’s Modern Typography (Hyphen Press, 1992), in “Notre livre (France)”, Graphisme en France, CNAP, 2003. ↩

- Alban Cerisier, Du côté de chez Gaston. Catalogue raisonné de l'œuvre typographique de Massin, 2 (1958-1979), City of Chartres, 1999, p. 40. ↩

- Laetitia Wolff, Massin, Phaidon, 2007, p. 62. ↩

- André Derval (texts and personal accounts by Bernard Anthonioz, Roland Barthes, François Billetdoux... (et al.) compiled by), Massin, Imec Éditions, 1990, p. 95. ↩

- Marguerite Duras, Œuvres complètes, 2011-2014, II, p. 1641. ↩

- Ibid. II, p. 1660 (Robert Harvey). ↩

- Ibid. II, p. 1641. ↩

- The Music, co-directed with Paul Seban (1967); Destroy, She Said (1969); Jaune le soleil or Yellow the Sun (1972); Nathalie Granger (1973); Woman of the Ganges (1974); India Song (1975); Her Venetian Name in Deserted Calcutta (1976); Entire Days in the Trees (1976); The Truck (1977); Baxter, Vera Baxter (1977); Le navire Night (1979); Aurelia Steiner (Melbourne) (1979); Aurélia Steiner (Vancouver) (1979); Cesarée (1979); Negative Hands (1979); Agatha and the Limitless Readings (1981); L’homme atlantique or The Atlantic Man (1981); Il dialogo di Roma (1982); The Children (1985). ↩

- André Derval, Massin, 1990, p. 95. ↩

- Paul Valéry, Au Directeur des «Marges», 1920, Variété II, Œuvres complètes, tome I. ↩

- Marguerite Duras, “La folie me donne de l’espoir”, Le Monde, December 17, 1969. ↩

- Marguerite Duras, Xavière Gauthier, Les Parleuses, Éditions de Minuit, p. 128. ↩

- History of the ‘Blanche’ collection on the publisher’s website. ↩

- Laetitia Wolff, Massin, 2007, p. 54. ↩

- André Derval, Massin, 1990, p. 95. ↩

- Cahiers du cinéma, Les Yeux verts, special issue 312-313, June 1980. ↩

- Marguerite Duras, Œuvres complètes, 2011-2014, II, pp. 1638-1641. ↩

- Ibid. II, pp. 1638-1641. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Marguerite Duras du mot à l’image, program “Chambre noire” 2 mars 1968. ↩

- Foreword to La Femme du Gange, in Marguerite Duras, Œuvres complètes, 2011-2014, II, p. 1431. ↩

- Michael Witt, Sauve qui peut (la vie), œuvre multimédia, in Nicole Brenez (dir.), Jean-Luc Godard Documents, 2006, Éditions du Centre Pompidou, Paris, pp. 302-315. ↩

- Marguerite Duras, Le Camion, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1977, p. 75. ↩

- Jean Cléder, “Marguerite Duras | Une pensée du regard cinématographique : pour regarder «absolument» (A thought of the cinematographic gaze: to look “absolutely”). Publication and conference organized by the Marguerite Duras Association. ↩

- Leopoldina Pallotta della Torre, Marguerite Duras, La Passion suspendue, (1st publication in Italian. La Passione sospesa, 1989) Seuil, 2013, p. 119. ↩

- Jacques Maillot (interview with Jean-Michel Frodon), “I don’t know of any comparable work on a book”, Le Monde, October 8, 1998. ↩

- See on this subject the research work of Jean-Marie Courant entitled “Blanche ou l’oubli” which he presented during a study day organized by the National Center for Plastic Arts (CNAP) on December 8, 2016 ↩

- Jean-Luc Godard, interview, “L’imaginaire est plus réel que le réel”, La Nouvelle Revue Française n°606, October 2013. ↩

- Émission Océaniques, “Duras-Godard”, 1987. ↩

- Georges Didi-Huberman, seminar “Cinema, history, politics, poetry”, at the INHA, November 2013-June 2014. ↩

- Read on this subject Cyril Béghin Marguerite Duras, Jean-Luc Godard, Dialogues, Post-Editions/Centre Pompidou, 2014. ↩

- Hélène Cixous and Michel Foucault (interview), “About Marguerite Duras”, Cahiers Renaud-Barrault, n°89, pp. 9-10. ↩

- Radio program produced by Annie Cœurdevey, in Marguerite Duras, Œuvres complètes, 2011-2014, II, p. 1650. ↩